Myths and Legends of China, by Edward T.C. Werner, [1922], at sacred-texts.com

Myths and Legends of China, by Edward T.C. Werner, [1922], at sacred-texts.com

According to Chinese ideas, the sun, moon, and planets influence sublunary events, especially the life and death of human beings, and changes in their colour menace approaching calamities. Alterations in the appearance of the sun announce misfortunes to the State or its head, as revolts, famines, or the death of the emperor; when the moon waxes red, or turns pale, men should be in awe of the unlucky times thus fore-omened.

The sun is symbolized by the figure of a raven in a circle, and the moon by a hare on its hind-legs pounding rice in a mortar, or by a three-legged toad. The last refers to the legend of Ch’ang Ô, detailed later. The moon is a special object of worship in autumn, and moon-cakes dedicated to it are sold at this season. All the stars are ranged into constellations, and an emperor is installed over them, who resides at the North Pole; five monarchs also live in the five stars in Leo, where is a palace called Wu Ti Tso, or ‘Throne of the Five Emperors.’ In this celestial government there are also an heir-apparent, empresses, sons and daughters, and tribunals, and the constellations receive the names of men, animals, and other terrestrial objects. The Great Bear, or Dipper, is worshipped as the residence of the Fates, where the duration of life and other events relating to mankind are measured and meted out. Fears are excited by unusual phenomena among the heavenly bodies.

Both the sun and the moon are worshipped by the p. 177 Government in appropriate temples on the east and west sides of Peking.

Some of the star-gods, such as the God of Literature, the Goddess of the North Star, the Gods of Happiness, Longevity, etc., are noticed in other parts of this work. The cycle-gods are also star-gods. There are sixty years in a cycle, and over each of these presides a special star-deity. The one worshipped is the one which gave light on the birthday of the worshipper, and therefore the latter burns candles before that particular image on each succeeding anniversary. These cycle-gods are represented by most grotesque images: “white, black, yellow, and red; ferocious gods with vindictive eyeballs popping out, and gentle faces as expressive as a lump of putty; some looking like men and some like women.” In one temple one of the sixty was in the form of a hog, and another in that of a goose. “Here is an image with arms protruding out of his eye-sockets, and eyes in the palms of his hands, looking downward to see the secret things within the earth. See that rabbit, Minerva-like, jumping from the divine head; again a mud-rat emerges from his occipital hiding-place, and lo! a snake comes coiling from the brain of another god—so the long line serves as models for an artist who desires to study the fantastic.”

In the family sleeping-apartments in Chinese houses hang pictures of Chang Hsien, a white-faced, long-bearded man with a little boy by his side, and in his hand a bow and arrow, with which he is shooting the Heavenly p. 178 Dog. The dog is the Dog-star, and if the ‘fate’ of the family is under this star there will be no son, or the child will be short-lived. Chang Hsien is the patron of child-bearing women, and was worshipped under the Sung dynasty by women desirous of offspring. The introduction of this name into the Chinese pantheon is due to an incident in the history of Hua-jui Fu-jên, a name given to Lady Fei, concubine of Mêng Ch’ang, the last ruler of the Later Shu State, A.D. 935–964. When she was brought from Shu to grace the harem of the founder of the Sung dynasty, in A.D. 960, she is said to have preserved secretly the portrait of her former lord, the Prince of Shu, whose memory she passionately cherished. Jealously questioned by her new consort respecting her devotion to this picture, she declared it to be the representation of Chang Hsien, the divine being worshipped by women desirous of offspring. Opinions differ as to the origin of the worship. One account says that the Emperor Jên Tsung, of the Sung dynasty, saw in a dream a beautiful young man with white skin and black hair, carrying a bow in his hand. He said to the Emperor: “The star T’ien Kou, Heavenly Dog, in the heavens is hiding the sun and moon, and on earth devouring small children. It is only my presence which keeps him at bay.”

On waking, the Emperor at once ordered the young man’s portrait to be painted and exhibited, and from that time childless families would write the name Chang Hsien on tablets and worship them.

Another account describes Chang Hsien as the spirit of the star Chang. In the popular representations Chang Hsien is seen in the form of a distinguished personage drawing a bow. The spirit of the star Chang p. 179 is supposed to preside over the kitchen of Heaven and to arrange the banquets given by the gods.

The worship of the sun is part of the State religion, and the officials make their offerings to the sun-tablet. The moon also is worshipped. At the harvest moon, the full moon of the eighth month, the Chinese bow before the heavenly luminary, and each family burns incense as an offering. Thus “100,000 classes all receive the blessings of the icy-wheel in the Milky Way along the heavenly street, a mirror always bright.” In Chinese illustrations we see the moon-palace of Ch’ang O, who stole the pill of immortality and flew to the moon, the fragrant tree which one of the genii tried to cut down, and a hare pestling medicine in a mortar. This refers to the following legend.

The sun and the moon are both included by the Chinese among the stars, the spirit of the former being called T’ai-yang Ti-chün, ‘the Sun-king,’ or Jih-kung Ch’ih-chiang, ‘Ch’ih-chiang of the Solar Palace,’ that of the latter T’ai-yin Huang-chün, ‘the Moon-queen,’ or Yüeh-fu Ch’ang O, ‘Ch’ang O of the Lunar Palace.’

Ch’ih-chiang Tzŭ-yü lived in the reign of Hsien-yüan Huang-ti, who appointed him Director of Construction and Furnishing.

When Hsien-yüan went on his visit to Ô-mei Shan, a mountain in Ssuch’uan, Ch’ih-chiang Tzŭ-yü obtained permission to accompany him. Their object was to be initiated into the doctrine of immortality.

The Emperor was instructed in the secrets of the doctrine by T’ai-i Huang-jên, the spirit of this famous mountain, who, when he was about to take his departure, p. 180 begged him to allow Ch’ih-chiang Tzŭ-yü to remain with him. The new hermit went out every day to gather the flowering plants which formed the only food of his master, T’ai-i Huang-jên, and he also took to eating these flowers, so that his body gradually became spiritualized.

One day T’ai-i Huang-jên sent him to cut some bamboos on the summit of Ô-mei Shan, distant more than three hundred li from the place where they lived. When he reached the base of the summit, all of a sudden three giddy peaks confronted him, so dangerous that even the monkeys and other animals dared not attempt to scale them. But he took his courage in his hands, climbed the steep slope, and by sheer energy reached the summit. Having cut the bamboos, he tried to descend, but the rocks rose like a wall in sharp points all round him, and he could not find a foothold anywhere. Then, though laden with the bamboos, he threw himself into the air, and was borne on the wings of the wind. He came to earth safe and sound at the foot of the mountain, and ran with the bamboos to his master. On account of this feat he was considered advanced enough to be admitted to instruction in the doctrine.

The Emperor Yao, in the twelfth year of his reign (2346 B.C.), one day, while walking in the streets of Huai-yang, met a man carrying a bow and arrows, the bow being bound round with a piece of red stuff. This was Ch’ih-chiang Tzŭ-yü. He told the Emperor he was a skilful archer and could fly in the air on the wings of p. 181 the wind. Yao, to test his skill, ordered him to shoot one of his arrows at a pine-tree on the top of a neighbouring mountain. Ch’ih shot an arrow which transfixed the tree, and then jumped on to a current of air to go and fetch the arrow back. Because of this the Emperor named him Shên I, ‘the Divine Archer,’ attached him to his suite, and appointed him Chief Mechanician of all Works in Wood. He continued to live only on flowers.

At this time terrible calamities began to lay waste the land. Ten suns appeared in the sky, the heat of which burnt up all the crops; dreadful storms uprooted trees and overturned houses; floods overspread the country. Near the Tung-t’ing Lake a serpent, a thousand feet long, devoured human beings, and wild boars of enormous size did great damage in the eastern part of the kingdom. Yao ordered Shên I to go and slay the devils and monsters who were causing all this mischief, placing three hundred men at his service for that purpose.

Shên I took up his post on Mount Ch’ing Ch’iu to study the cause of the devastating storms, and found that these tempests were released by Fei Lien, the Spirit of the Wind, who blew them out of a sack. As we shall see when considering the thunder myths, the ensuing conflict ended in Fei Lien suing for mercy and swearing friendship to his victor, whereupon the storms ceased.

After this first victory Shên I led his troops to the banks of the Hsi Ho, West River, at Lin Shan. Here he discovered that on three neighbouring peaks nine p. 182 extraordinary birds were blowing out fire and thus forming nine new suns in the sky. Shên I shot nine arrows in succession, pierced the birds, and immediately the nine false suns resolved themselves into red clouds and melted away. Shên I and his soldiers found the nine arrows stuck in nine red stones at the top of the mountain.

Shên I then led his soldiers to Kao-liang, where the river had risen and formed an immense torrent. He shot an arrow into the water, which thereupon withdrew to its source. In the flood he saw a man clothed in white, riding a white horse and accompanied by a dozen attendants. He quickly discharged an arrow, striking him in the left eye, and the horseman at once took to flight. He was accompanied by a young woman named Hêng O 1, the younger sister of Ho Po, the Spirit of the Waters. Shên I shot an arrow into her hair. She turned and thanked him for sparing her life, adding: “I will agree to be your wife.” After these events had been duly reported to the Emperor Yao, the wedding took place.

Three months later Yao ordered Shên I to go and kill the great Tung-t’ing serpent. An arrow in the left eye laid him out stark and dead. The wild boars also were all caught in traps and slain. As a reward for these p. 183 achievements Yao canonized Shên I with the title of Marquis Pacifier of the Country.

About this time T’ai-wu Fu-jên, the third daughter of Hsi Wang Mu, had entered a nunnery on Nan-min Shan, to the north of Lo-fou Shan, where her mother’s palace was situated. She mounted a dragon to visit her mother, and all along the course left a streak of light in her wake. One day the Emperor Yao, from the top of Ch’ing-yün Shan, saw this track of light, and asked Shên I the cause of this unusual phenomenon. The latter mounted the current of luminous air, and letting it carry him whither it listed, found himself on Lo-fou Shan, in front of the door of the mountain, which was guarded by a great spiritual monster. On seeing Shên I this creature called together a large number of phoenixes and other birds of gigantic size and set them at Shên I. One arrow, however, settled the matter. They all fled, the door opened, and a lady followed by ten attendants presented herself. She was no other than Chin Mu herself. Shên I, having saluted her and explained the object of his visit, was admitted to the goddess’s palace, and royally entertained.

“I have heard,” said Shên I to her, “that you possess the pills of immortality; I beg you to give me one or two.” “You are a well-known architect,” replied Chin Mu; “please build me a palace near this mountain.” Together they went to inspect a celebrated site known as Pai-yü-kuei Shan, ‘White Jade-tortoise Mountain,’ and fixed upon it as the location of the new abode of the goddess. Shên I had all the spirits of the mountain to work for him. The walls were built of jade, sweet-smelling p. 184 woods were used for the framework and wainscoting, the roof was of glass, the steps of agate. In a fortnight’s time sixteen palace buildings stretched magnificently along the side of the mountain. Chin Mu gave to the architect a wonderful pill which would bestow upon him immortality as well as the faculty of being able at will to fly through the air. “But,” she said, “it must not be eaten now: you must first go through a twelve months’ preparatory course of exercise and diet, without which the pill will not have all the desired results.” Shên I thanked the goddess, took leave of her, and, returning to the Emperor, related to him all that had happened.

On reaching home, the archer hid his precious pill under a rafter, lest anyone should steal it, and then began the preparatory course in immortality.

At this time there appeared in the south a strange man named Tso Ch’ih, ‘Chisel-tooth.’ He had round eyes and a long projecting tooth. He was a well-known criminal. Yao ordered Shên I and his small band of brave followers to deal with this new enemy. This extraordinary man lived in a cave, and when Shên I and his men arrived he emerged brandishing a padlock. Shên I broke his long tooth by shooting an arrow at it, and Tso Ch’ih fled, but was struck in the back and laid low by another arrow from Shên I. The victor took the broken tooth with him as a trophy.

Hêng Ô, during her husband’s absence, saw a white light which seemed to issue from a beam in the roof, while a most delicious odour filled every room. By the p. 185 aid of a ladder she reached up to the spot whence the light came, found the pill of immortality, and ate it. She suddenly felt that she was freed from the operation of the laws of gravity and as if she had wings, and was just essaying her first flight when Shên I returned. He went to look for his pill, and, not finding it, asked Hêng Ô what had happened.

Click to enlarge

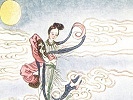

Hêng Ô Flies to the Moon

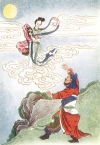

The young wife, seized with fear, opened the window and flew out. Shên I took his bow and pursued her. The moon was full, the night clear, and he saw his wife flying rapidly in front of him, only about the size of a toad. Just when he was redoubling his pace to catch her up a blast of wind struck him to the ground like a dead leaf.

Hêng Ô continued her flight until she reached a luminous sphere, shining like glass, of enormous size, and very cold. The only vegetation consisted of cinnamon-trees. No living being was to be seen. All of a sudden she began to cough, and vomited the covering of the pill of immortality, which was changed into a rabbit as white as the purest jade. This was the ancestor of the spirituality of the yin, or female, principle. Hêng Ô noticed a bitter taste in her mouth, drank some dew, and, feeling hungry, ate some cinnamon. She took up her abode in this sphere.

As to Shên I, he was carried by the hurricane up into a high mountain. Finding himself before the door of a palace, he was invited to enter, and found that it was the palace of Tung-hua Ti-chün, otherwise Tung Wang Kung, the husband of Hsi Wang Mu.

The God of the Immortals said to Shên I: “You must not be annoyed with Hêng Ô. Everybody’s fate is p. 186 settled beforehand. Your labours are nearing an end, and you will become an Immortal. It was I who let loose the whirlwind that brought you here. Hêng O, through having borrowed the forces which by right belong to you, is now an Immortal in the Palace of the Moon. As for you, you deserve much for having so bravely fought the nine false suns. As a reward you shall have the Palace of the Sun. Thus the yin and the yang will be united in marriage.” This said, Tung-hua Ti-chün ordered his servants to bring a red Chinese sarsaparilla cake, with a lunar talisman.

“Eat this cake,” he said; “it will protect you from the heat of the solar hearth. And by wearing this talisman you will be able at will to visit the lunar palace of Hêng O; but the converse does not hold good, for your wife will not have access to the solar palace.” This is why the light of the moon has its birth in the sun, and decreases in proportion to its distance from the sun, the moon being light or dark according as the sun comes and goes. Shên I ate the sarsaparilla cake, attached the talisman to his body, thanked the god, and prepared to leave. Tung Wang Kung said to him: “The sun rises and sets at fixed times; you do not yet know the laws of day and night; it is absolutely necessary for you to take with you the bird with the golden plumage, which will sing to advise you of the exact times of the rising, culmination, and setting of the sun.” “Where is this bird to be found?” asked Shên I. “It is the one you hear calling Ia! Ia! It is the ancestor of the spirituality of the yang, or male, principle. Through having eaten the active principle of the sun, it has assumed the form of a three-footed bird, which perches on the fu-sang tree [a tree said to grow at the place where the sun rises] in p. 187 the middle of the Eastern Sea. This tree is several thousands of feet in height and of gigantic girth. The bird keeps near the source of the dawn, and when it sees the sun taking his morning bath gives vent to a cry that shakes the heavens and wakes up all humanity. That is why I ordered Ling Chên-tzŭ to put it in a cage on T’ao-hua Shan, Peach-blossom Hill; since then its cries have been less harsh. Go and fetch it and take it to the Palace of the Sun. Then you will understand all the laws of the daily movements.” He then wrote a charm which Shên I was to present to Ling Chên-tzŭ to make him open the cage and hand the golden bird over to him.

The charm worked, and Ling Chên-tzŭ opened the cage. The bird of golden plumage had a sonorous voice and majestic bearing. “This bird,” he said, “lays eggs which hatch out nestlings with red combs, who answer him every morning when he starts crowing. He is usually called the cock of heaven, and the cocks down here which crow morning and evening are descendants of the celestial cock.”

Shên I, riding on the celestial bird, traversed the air and reached the disk of the sun just at mid-day. He found himself carried into the centre of an immense horizon, as large as the earth, and did not perceive the rotatory movement of the sun. He then enjoyed complete happiness without care or trouble. The thought of the happy hours passed with his wife Hêng O, however, came back to memory, and, borne on a ray of sunlight, he flew to the moon. He saw the cinnamon-trees and the frozen-looking horizon. Going to a secluded spot, he found Hêng O there all alone. On seeing him she was p. 188 about to run away, but Shên I took her hand and reassured her. “I am now living in the solar palace,” he said; “do not let the past annoy you.” Shên I cut down some cinnamon-trees, used them for pillars, shaped some precious stones, and so built a palace, which he named Kuang-han Kung, ‘Palace of Great Cold.’ From that time forth, on the fifteenth day of every moon, he went to visit her in her palace. That is the conjunction of the yang and yin, male and female principles, which causes the great brilliancy of the moon at that epoch.

Shên I, on returning to his solar kingdom, built a wonderful palace, which he called the Palace of the Lonely Park.

From that time the sun and moon each had their ruling sovereign. This régime dates from the forty-ninth year (2309 B.C.) of Yao’s reign.

When the old Emperor was informed that Shên I and his wife had both gone up to Heaven he was much grieved to lose the man who had rendered him such valuable service, and bestowed upon him the posthumous title of Tsung Pu, ‘Governor of Countries.’ In the representations of this god and goddess the former is shown holding the sun, the latter the moon. The Chinese add the sequel that Hêng O became changed into a toad, whose outline is traceable on the moon’s surface.

The star-deities are adored by parents on behalf of their children; they control courtship and marriage, bring prosperity or adversity in business, send pestilence and war, regulate rainfall and drought, and command angels and demons; so every event in life is determined p. 189 by the ‘star-ruler’ who at that time from the shining firmament manages the destinies of men and nations. The worship is performed in the native homes either by astrologers engaged for that purpose or by Taoist priests. In times of sickness, ten paper star-gods are arranged, five good on one side and five bad on the other; a feast is placed before them, and it is supposed that when the bad have eaten enough they will take their flight to the south-west; the propitiation of the good star-gods is in the hope that they will expel the evil stars, and happiness thus be obtained.

The practical effect of this worship is seen in the following examples taken from the Chinese list of one hundred and twenty-nine lucky and unlucky stars, which, with the sixty cycle-stars and the twenty-eight constellations, besides a vast multitude of others, make up the celestial galaxy worshipped by China’s millions: the Orphan Star enables a woman to become a man; the Star of Pleasure decides on betrothals, binding the feet of those destined to be lovers with silver cords; the Bonepiercing Star produces rheumatism; the Morning Star, if not worshipped, kills the father or mother during the year; the Balustrade Star promotes lawsuits; the Three-corpse Star controls suicide, the Peach-blossom Star lunacy; and so on.

In the myths and legends which have clustered about the observations of the stars by the Chinese there are subjects for pictorial illustration without number. One of these stories is the fable of Aquila and Vega, known in Chinese mythology as the Herdsman and the Weaver-girl. The latter, the daughter of the Sun-god, p. 190 was so constantly busied with her loom that her father became worried at her close habits and thought that by marrying her to a neighbour, who herded cattle on the banks of the Silver Stream of Heaven (the Milky Way), she might awake to a brighter manner of living.

No sooner did the maiden become wife than her habits and character utterly changed for the worse. She became not only very merry and lively, but quite forsook loom and needle, giving up her nights and days to play and idleness; no silly lover could have been more foolish than she. The Sun-king, in great wrath at all this, concluded that the husband was the cause of it, and determined to separate the couple. So he ordered him to remove to the other side of the river of stars, and told him that hereafter they should meet only once a year, on the seventh night of the seventh month. To make a bridge over the flood of stars, the Sun-king called myriads of magpies, who thereupon flew together, and, making a bridge, supported the poor lover on their wings and backs as if on a roadway of solid land. So, bidding his weeping wife farewell, the lover-husband sorrowfully crossed the River of Heaven, and all the magpies instantly flew away. But the two were separated, the one to lead his ox, the other to ply her shuttle during the long hours of the day with diligent toil, and the Sun-king again rejoiced in his daughter’s industry.

At last the time for their reunion drew near, and only one fear possessed the loving wife. What if it should rain? For the River of Heaven is always full to the brim, and one extra drop causes a flood which sweeps away even the bird-bridge. But not a drop fell; all the heavens were clear. The magpies flew joyfully in myriads, making a way for the tiny feet of the little lady. p. 191 Trembling with joy, and with heart fluttering more than the bridge of wings, she crossed the River of Heaven and was in the arms of her husband. This she did every year. The husband stayed on his side of the river, and the wife came to him on the magpie bridge, save on the sad occasions when it rained. So every year the people hope for clear weather, and the happy festival is celebrated alike by old and young.

These two constellations are worshipped principally by women, that they may gain cunning in the arts of needlework and making of fancy flowers. Water-melons, fruits, vegetables, cakes, etc., are placed with incense in the reception-room, and before these offerings are performed the kneeling and the knocking of the head on the ground in the usual way.

Sacrifices were offered to these spirits by the Emperor on the marble altar of the Temple of Heaven, and by the high officials throughout the provinces. Of the twenty-eight the following are regarded as propitious—namely, the Horned, Room, Tail, Sieve, Bushel, House, Wall, Mound, Stomach, End, Bristling, Well, Drawn-bow, and Revolving Constellations; the Neck, Bottom, Heart, Cow, Female, Empty, Danger, Astride, Cock, Mixed, Demon, Willow, Star, Wing, are unpropitious.

The twenty-eight constellations seem to have become the abodes of gods as a result of the defeat of a Taoist Patriarch T’ung-t’ien Chiao-chu, who had espoused the cause of the tyrant Chou, when he and all his followers were slaughtered by the heavenly hosts in the terrible catastrophe known as the Battle of the Ten Thousand Immortals. Chiang Tzŭ-ya as a reward conferred on p. 192 them the appanage of the twenty-eight constellations. The five planets, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, and Saturn, are also the abodes of stellar divinities, called the White, Green, Black, Red, and Yellow Rulers respectively. Stars good and bad are all likewise inhabited by gods or demons.

Concerning Tzŭ-wei Hsing, the constellation Tzŭ-wei (north circumpolar stars), of which the stellar deity is Po I-k’ao, the following legend is related in the Fêng shên yen i.

Po I-k’ao was the eldest son of Wên Wang, and governed the kingdom during the seven years that the old King Was detained as a prisoner of the tyrant Chou. He did everything possible to procure his father’s release. Knowing the tastes of the cruel King, he sent him for his harem ten of the prettiest women who could be found, accompanied by seven chariots made of perfumed wood, and a white-faced monkey of marvellous intelligence. Besides these he included in his presents a magic carpet, on which it was necessary only to sit in order to recover immediately from the effects of drunkenness.

Unfortunately for Po I-k’ao, Chou’s favourite concubine, Ta Chi, conceived a passion for him and had recourse to all sorts of ruses to catch him in her net; but his conduct was throughout irreproachable. Vexed by his indifference, she tried slander in order to bring about his ruin. But her calumnies did not at first have the result she expected. Chou, after inquiry, was convinced of the innocence of Po. But an accident spoiled everything. In the middle of an amusing séance the monkey which had been given to the King by Po perceived some p. 193 sweets in the hand of Ta Chi, and, jumping on to her body, snatched them from Her. The King and his concubine were furious, Chou had the monkey killed forthwith, and Ta Chi accused Po I-k’ao of having brought the animal into the palace with the object of making an attempt on the lives of the King and herself. But the Prince explained that the monkey, being only an animal, could not grasp even the first idea of entering into a conspiracy.

Shortly after this Po committed an unpardonable fault which changed the goodwill of the King into mortal enmity. He allowed himself to go so far as to suggest to the King that he should break off his relations with this infamous woman, the source of all the woes which were desolating the kingdom, and when Ta Chi on this account grossly insulted him he struck her with his lute.

For this offence Ta Chi caused him to be crucified in the palace. Large nails were driven through his hands and feet, and his flesh was cut off in pieces. Not content with ruining Po I-k’ao, this wretched woman wished also to ruin Wen Wang. She therefore advised the King to have the flesh of the murdered man made up into rissoles and sent as a present to his father. If he refused to eat the flesh of his own son he was to be accused of contempt for the King, and there would thus be a pretext for having him executed. Wen Wang, being versed in divination and the science of the pa kua, Eight Trigrams, knew that these rissoles contained the flesh of his son, and to avoid the snare spread for him he ate three of the rissoles in the presence of the royal envoys. On their return the latter reported this to the King, who found himself helpless on learning of Wen Wang’s conduct. p. 194

Po I-k’ao was canonized by Chiang Tzu-ya, and appointed ruler of the constellation Tzu-wei of the North Polar heavens.

T’ai Sui is the celestial spirit who presides over the year. He is the President of the Ministry of Time. This god is much to be feared. Whoever offends against him is sure to be destroyed. He strikes when least expected to. T’ai Sui is also the Ministry itself, whose members, numbering a hundred and twenty, are set over time, years, months, and days. The conception is held by some writers to be of Chaldeo-Assyrian origin.

The god T’ai Sui is not mentioned in the T’ang and Sung rituals, but in the Yüan dynasty (A.D. 1280–1368) sacrifices were offered to him in the College of the Grand Historiographer whenever any work of importance was about to be undertaken. Under this dynasty the sacrifices were offered to T’ai Sui and to the ruling gods of the months and of the days. But these sacrifices were not offered at regular times: it was only at the beginning of the Ch’ing (Manchu) dynasty (1644–1912) that it was decided to offer the sacrifices at fixed periods.

T’ai Sui corresponds to the planet Jupiter. He travels across the sky, passing through the twelve sidereal mansions. He is a stellar god. Therefore an altar is raised to him and sacrifices are offered on it under the open sky. This practice dates from the beginning of the Ming dynasty, when the Emperor T’ai Tsu ordered sacrifices to this god to be made throughout the Empire. According to some authors, he corresponds to the god p. 195 of the twelve sidereal mansions. He is also variously represented as the moon, which turns to the left in the sky, and the sun, which turns to the right. The diviners gave to T’ai Sui the title of Grand Marshal, following the example of the usurper Wang Mang (A.D. 9–23) of the Western Han dynasty, who gave that title to the year-star.

The following is the legend of T’ai Sui.

T’ai Sui was the son of the Emperor Chou, the last of the Yin dynasty. His mother was Queen Chiang. When he was born he looked like a lump of formless flesh. The infamous Ta Chi, the favourite concubine of this wicked Emperor, at once informed him that a monster had been born in the palace, and the over-credulous sovereign ordered that it should immediately be cast outside the city. Shên Chên-jên, who was passing, saw the small abandoned one, and said: “This is an Immortal who has just been born.” With his knife he cut open the caul which enveloped it, and the child was exposed.

His protector carried him to the cave Shui Lien, where he led the life of a hermit, and entrusted the infant to Ho Hsien-ku, who acted as his nurse and brought him up.

The child’s hermit-name was Yin Ting-nu, his ordinary name Yin No-cha, but during his boyhood he was known as Yin Chiao, i.e. ‘Yin the Deserted of the Suburb,’ When he had reached an age when he was sufficiently intelligent, his nurse informed him that he was not her son, but really the son of the Emperor Chou, who, deceived by the calumnies of his favourite Ta Chi, had taken him for an evil monster and had him cast out of the palace. His mother had been thrown down from an upper storey p. 196 and killed. Yin Chiao went to his rescuer and begged him to allow him to avenge his mother’s death. The Goddess T’ien Fei, the Heavenly Concubine, picked out two magic weapons from the armoury in the cave, a battle-axe and club, both of gold, and gave them to Yin Chiao. When the Shang army was defeated at Mu Yeh, Yin Chiao broke into a tower where Ta Chi was, seized her, and brought her before the victor, King Wu, who gave him permission to split her head open with his battle-axe. But Ta Chi was a spiritual hen-pheasant (some say a spiritual vixen). She transformed herself into smoke and disappeared. To reward Yin Chiao for his filial piety and bravery in fighting the demons, Yü Ti canonized him with the title T’ai Sui Marshal Yin.

According to another version of the legend, Yin Chiao fought on the side of the Yin against Wu Wang, and after many adventures was caught by Jan Têng between two mountains, which he pressed together, leaving only Yin Chiao’s head exposed above the summits. The general Wu Chi promptly cut it off with a spade. Chiang Tz[u)]-ya subsequently canonized Yin Chiao.

The worship of T’ai Sui seems to have first taken place in the reign of Shên Tsung (A.D. 1068–86) of the Sung dynasty, and was continued during the remainder of the Monarchical Period. The object of the worship is to avert calamities, T’ai Sui being a dangerous spirit who can do injury to palaces and cottages, to people in their houses as well as to travellers on the roads. But he has this peculiarity, that he injures persons and things not in the district in which he himself is, but in those districts which adjoin it. Thus, if some constructive work is p. 197 undertaken in a region where T’ai Sui happens to be, the inhabitants of the neighbouring districts take precautions against his evil influence. This they generally do by hanging out the appropriate talisman. In order to ascertain in what region T’ai Sui is at any particular time, an elaborate diagram is consulted. This consists of a representation of the twelve terrestrial branches or stems, ti chih> and the ten celestial trunks, t’ien kan, indicating the cardinal points and the intermediate points, north-east, north-west, south-east, and south-west. The four cardinal points are further verified with the aid of the Five Elements, the Five Colours, and the Eight Trigrams. By using this device, it is possible to find the geographical position of T’ai Sui during the current year, the position of threatened districts, and the methods to be employed to provide against danger. p. 198

198:1 She is the same as Ch’ang Ô, the name Hêng being changed to Ch’ang because it was the tabooed personal name of the Emperors Mu Tsung of the T’ang dynasty and Chên Tsung of the Sung dynasty.